@e_flux wrote:

![]()

In the NY Times, book critic Adam Kirsch and novelist Zoë Heller address the question of whether a book with "bad politics"—e.g., reactionary conservatism—can still be a good book. They both conclude that it can—with Kirsch citing Plato, and Heller citing Jonathan Swift. Here's a snippet of Heller's response:

In his essay “Politics vs. Literature,” George Orwell tries to explain why it is that he dislikes the misanthropic and reactionary message of “Gulliver’s Travels” but loves the book. The answer, he decides, is that although Jonathan Swift’s ideas are false, they are not so completely false as to prohibit the reader’s sympathy: The book speaks to that part of a reader’s mind that “at least intermittently stands aghast at the horror of existence.” A great work of art may be written from any ideological viewpoint, Orwell concludes, so long as the viewpoint is “compatible with sanity, in the medical sense, and with the power of continuous thought.”

This strikes me as a bad argument — not least because it assumes that the ultimate meaning or value of a book resides in what can be summed up, CliffsNotes style, as its “worldview.” Orwell is not much interested in how Swift chooses to convey his satirical message. He pays fleeting homage to Swift’s “native gift for using words,” but for him, the book is essentially a delivery system for Swift’s moral philosophy, and it succeeds because it enlists our partial agreement with that philosophy. I’d argue more or less the contrary: It’s everything in “Gulliver’s Travels” that is in excess of (and often at odds with) Swift’s nihilistic “point” — its inventiveness, its originality and wit, its sheer weirdness — that accounts for its lasting appeal. It succeeds because its imaginative energies continually overflow its rather narrow political purpose.

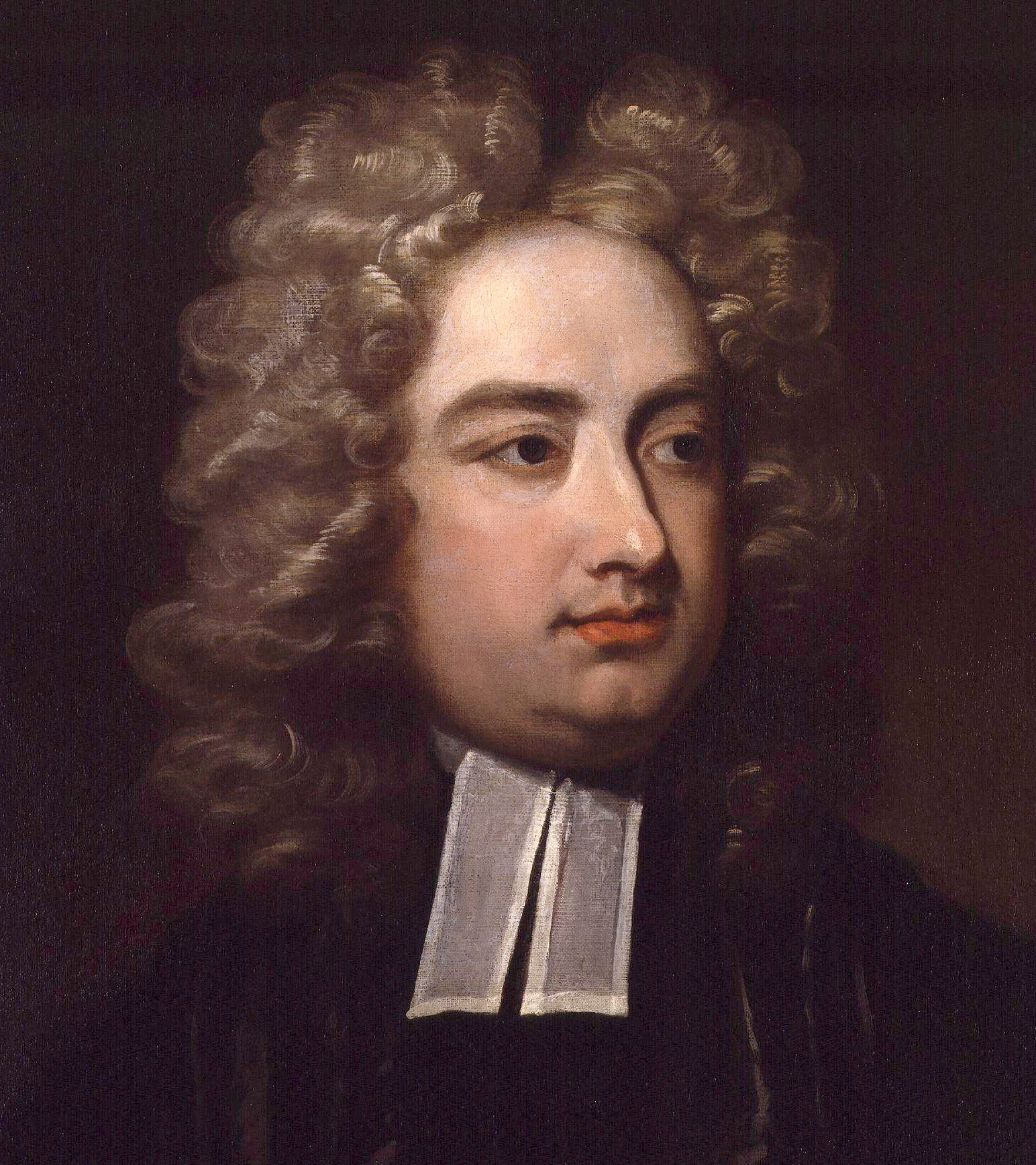

Image of Jonathan Swift via Wikipedia.

Posts: 1

Participants: 1